To Pigeon-Fill the Sky is a photographic storybook about artificial intelligence, the creative process, and, of course, pigeons.

Returning to photography after a year-long hiatus, I struggled to match the quality of my old work. My new images were weak. They lacked dynamism, punctum, decisive moments. No birds filled their skies. I had spent a year remembering the best of my old images, rose-tinted, and had forgotten the patience and persistence that was required to make them. I saw photographs of miracles, and forgot how long I had stood there waiting for them. I had forgotten that good art takes hard work.

I’m a software engineer as well as a photographer, and I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about and interacting with artificial intelligence. Over the past three years, I’ve witnessed my two industries froth and fight over the glittering promise of AI, the shortcuts it opens, the expertise and experience it renders obsolete, and the slop that it burns into being. I imagined an artist who might forego patience, persistence, and hard work for an artificially injected decisive moment—why wait for punctum when you can add it in post?

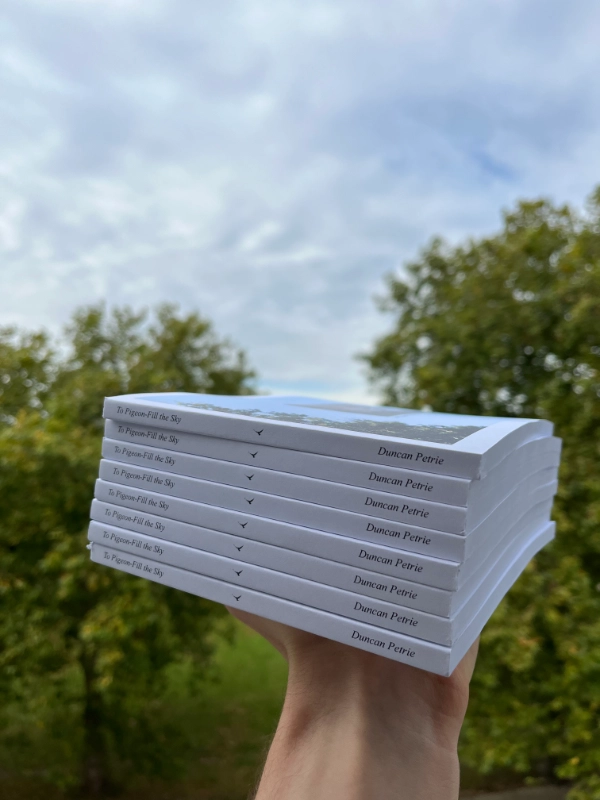

To Pigeon-Fill the Sky is the story of that artist. It contains 100 pages of analog photography, digital photography, real pigeons, and digital pigeons. It was shot and edited in the summer of 2024, in and around London, England.

View the whole PDF here.